The Great Canadian Road Trip

Even 150 years into Confederation, Canada’s population numbers remain dwarfed by the enormous landmass we call home. Distance and geography are the transportation obstacles history has placed before us. These obstacles were clear to the visionaries who built this nation. So was the resolve to overcome them.

Travel has always been central to the discovery of Canada and making it work, whether as First Nations and voyageurs navigating the maze of rivers, 19th-century immigrants catching a first glimpse of their new prairie home from the window of a rail car, or 20-somethings taking to the Trans-Canada Highway in search of themselves.

A ROAD OF IRON

At its birth in 1867, Canada was made up of only four provinces. But within four years the country spanned Atlantic to Pacific as Manitoba, the North-West Territory (which included land that would later become Alberta and Saskatchewan) and British Columbia (BC) entered Confederation. BC was a tough sell on the merits of joining the other provinces. Many citizens favoured annexation by the United States, where strong trade links had already been forged. Many others preferred to maintain close ties with Britain.

Among BC’s conditions for joining Canada, the governor’s delegation to Ottawa sought guarantees of a transportation link with the east. They asked for a wagon road. They returned waving the promise of a transcontinental railway line instead.

The road trip to economic prosperity—and a new era of mobility—had begun.

THE GOAL OF NATION BUILDING

“The building of the Canadian Pacific Railroad in the early 1880s was certainly iconic in the building of a transportation network, but there were railways that preceded the CPR,” says Tom Murray, a North American rail transportation consultant and author of seven railroad books, including Rails Across Canada: The History of the Canadian Pacific and Canadian National Railways. “The difference is that the early railways were motivated more by local and provincial economic realities than the goal of nation building, which drove construction of the CPR transcontinental route.”

Murray contends that the railways in general, and the CPR in particular, gave Canada its first opportunity to participate in the world economy. “Canada’s was essentially a resource and agricultural economy at the time,” says Murray. “There were limited natural markets within Canada for grain, coal, timber and other products. But there were world markets eager for all of those things. Getting those commodities to deep-water ports was essential and really a big motivation for building all the major rail lines in Canada.”

More than a century later, access to world markets still drives domestic transportation development—particularly the movement of oil to tidewater and refinery sites.

Forging a place in the world

The transcontinental railway and the Trans-Canada Highway are just two among many megaprojects that have helped Canada acquire the technological and engineering expertise that are essential to nation building. The St. Lawrence Seaway, the Churchill Falls and James Bay hydroelectric facilities, the oil sands and soon a nation-wide energy pipeline system—complex projects like these have concurrently built domestic confidence and capacity, and international connections, gradually securing Canada’s place as a global economic force.

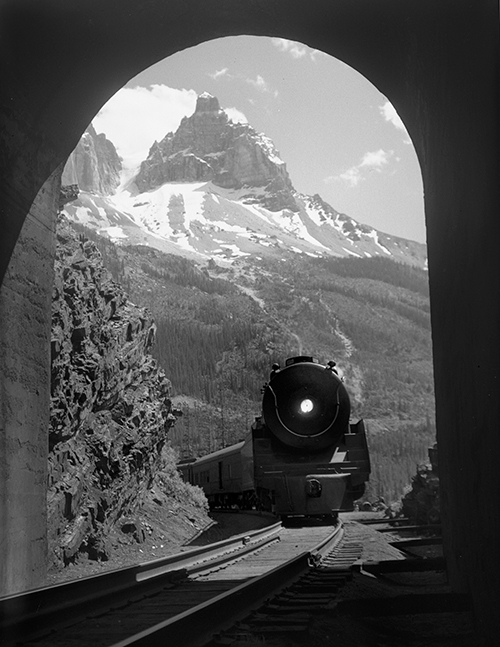

INTO THE MOUNTAINS

The trans-continental railway was a weighty expenditure for a population of just over three million, and a staggering feat of engineering in its day—particularly through the mountains of BC. Celebrated Canadian engineer Sir Sanford Fleming had lobbied for a more northerly route into the Rocky and Selkirk ranges, primarily for the milder grades and simpler engineering challenges. The CPR opted for the southern route, which was closer to the American border and a more direct path to the coast. But Cornelius Van Horne, the American imported by the CPR to complete the railroad, knew the route through Banff, Alberta offered another advantage—tourism. Banff was not connected by road to the outside world until the opening of a highway from Calgary in 1914. Until then, access to Rocky Mountains Park was exclusively by rail, and CPR’s line wound through some of the West’s most spectacular mountain terrain. “If we can’t export the scenery,” Van Horne famously said, “we’ll import the tourists.”

He did. In June 1888, the CPR opened the Banff Springs Hotel in what would later become Banff National Park. Tourists travelled from all over the world to the hotel and two other mountain resorts built by the CPR, helping to transform the company into an international travel giant that also operated shipping in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

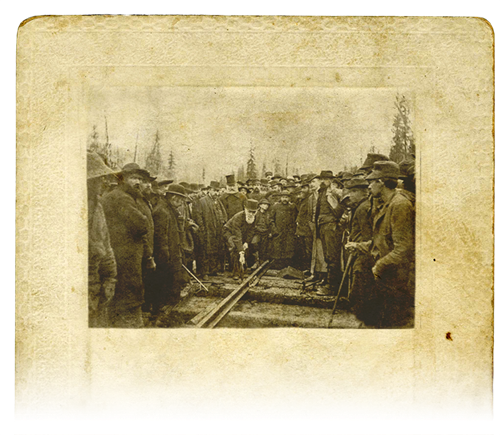

Bringing the hammer down

The image of the last spike is an iconic one for Canadians—the crowd of rail workers and minor dignitaries surrounding railroad financier Donald Smith at Craigellachie, British Columbia in November 1885. The swing of Smith’s hammer and the completion of the transcontinental railroad fulfilled a key condition BC had set for entering confederation in 1871—namely, establishing a viable transportation link with the east.

IMMIGRATION ALSO PRESENTED ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITY

“Passenger rail service in those early years—especially between 1900 and 1914—met another very important economic goal, which was to bring new people to the western provinces,” says Tom Murray. “If you didn’t have people, you weren’t going to have any freight business. You needed to settle the Prairies to build an economy there and get railway traffic and revenue flowing both ways.”

Historians often invoke Canada’s experience in the First World War as a major turning point for the country, the period in which it attained clear and painful maturity in the world. But Murray suggests this pivotal transition was also due in part to a new sense we had gained of ourselves at home in the previous decades—an appreciation that travel helped inspire within us.

“The flow of humanity east and west has really knit the country together,” observes Murray. “It gradually drew connections among people, made them aware of the country and opened their eyes not just to the vastness and great natural wealth of Canada—but more importantly to its potential.”

To this day, these are the true gifts of the great Canadian road trip. But as we emerged from yet another world war in the late 1940s, another road opened before us, underscoring our freedom and beckoning us to get out and discover Canada: the highway.

Our concern for the environment isn’t limited to fighting climate change … Mr. Speaker, our national parks are the most beautiful places on Earth … Together we will share these national treasures with a whole new generation of children—and capture the spirit of the great Canadian road trip.

Finance Minister Bill Morneau, Federal budget speech, March 22, 2016

A cornerstone in the strategy to conserve Canada’s impressive biodiversity

Three railway workers helped give birth to Canada’s national park system in 1883. As CPR construction pushed into the Rockies, the workers stumbled on the Cave and Basin Hot Springs about 130 kilometres west of Fort Calgary. Three years later, a Dominion land surveyor reported that the site was ideally suited to be a national park.

The federal government responded with an Act of Parliament in 1887, renaming the site as Rocky Mountains Park and, later, Banff National Park. It was the first of many mountain parks, and by the early 20th century other national sites were set up in eastern Canada. The government formed the Dominion Parks Branch in 1911—the first federal parks administration in the world. Today, every province and territory is home to at least one of more than 40 national parks and national park reserves that occupy roughly three percent of Canada’s landmass.

The goal of the parks system in its early days was to lure travelers from around the globe. Rising environmental awareness through the 1960s began to shift the priority from presentation to protection. Attendance may have suffered as a result. Visitor numbers declined between 2001 and 2011, Parks Canada’s centennial year; however, they’ve been on the rise ever since. Innovative environmental programming can take some of the credit.

In 2011, Parks Canada launched the Learn to Camp program, which targets young people, city dwellers and new Canadians, bolstering their outdoor skills and strengthening their appreciation for the astounding scope of Canada’s natural endowment.

TWO BEGINNINGS AND NO END

It’s hard today to imagine a Canada not traversable from Atlantic to Pacific by car or truck. We take for granted our ability to travel widely; we assume that the roads go just about everywhere. In fact, travel by road across Canada was not possible until after World War II. And much of what was available was gravel road, including the final 246-kilometre stretch completed in 1946 to finally link east and west through northern Ontario. For decades, business leaders had led the call for a true national highway—a paved road—to provide an alternative to rail freight for the economic movement of people and distribution of goods. The federal government responded in 1949 with the Trans-Canada Highway Act. Construction began the following year—the same year oil, and petroleum-based transportation fuels, replaced coal as Canada’s largest single source of energy.

Prime Minister John Diefenbaker officially opened the Trans-Canada Highway in 1962, although it would be another nine years before work was completed. Today, the Trans-Canada is one of the world’s longest highways, spanning nearly 8,000 kilometres from St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador to Victoria, BC. Both cities claim the “mile zero” designation, which prompted journalist Walter Stewart to write in 1965, “the Trans-Canada Highway (is) the world’s only national roadway that has two beginnings and no end … Very Canadian, very sensible.”

THE AGE OF MOBILITY

In Canada, the 1950s and 1960s were the age of motor hotels and gas stations, thousands of which sprang up to serve travellers on every route. Glove compartments were stuffed with roadmaps, conveniently available at any roadside petroleum retailer, and the job of the front-seat passenger became one of navigation.

Lured by the outdoors, and with more leisure time than ever before, Canadians embraced camping as an affordable road trip the entire family could enjoy. Towing capacity became an important consideration when buying a new vehicle, whether you were hauling a tiny tent trailer or a sleek Airstream. Canadians flocked to private, provincial and national parks to battle mosquitoes, circle campfires and get a taste, if fleeting, for life on the land.

JUST GO

The greatest Canadian road trips may still lie ahead. Autonomous-vehicle technology now offers the prospect of a trip in which you can revel in the distractions. Forget about the wheel. Enter your destination and let the computer manage the speed. As you make your way from one end of the country to the other, focus on the family, the scenery and the environment.

Whatever your Canadian road—woodland trail, waterway, rail line, flight path or paved highway—make this sesquicentennial the year to travel, explore and celebrate our Canada.